In an uncertain world, budget revenue and spending often end up far away from government plans. Volatile growth, high universal subsidies, and loss-making state-owned enterprises expose many low- and middle-income economies in the Middle East, North Africa, and Pakistan to such fiscal risks. These factors combine with adverse external developments such as recent interest-rate rises and food and fuel price surges to put public finances under pressure in many countries.

As we explain in a new paper, the “MENAPEG” region—a group that includes economies in the Middle East, North Africa and Pakistan but excludes high-income Gulf countries—is especially vulnerable to fiscal risks. In fact, small fiscal risks occur in countries every year. Importantly, larger shocks that cause debt to increase by an average of 12 percent of gross domestic product occur, on average, once every eight years.

Despite the frequency of these events, policymakers are often caught off guard. Such shocks force them to make ad hoc cuts to development and other priority spending. This also limits many countries’ ability to use fiscal policy to smooth economic slowdowns, precisely when it is needed most.

Sources of risks

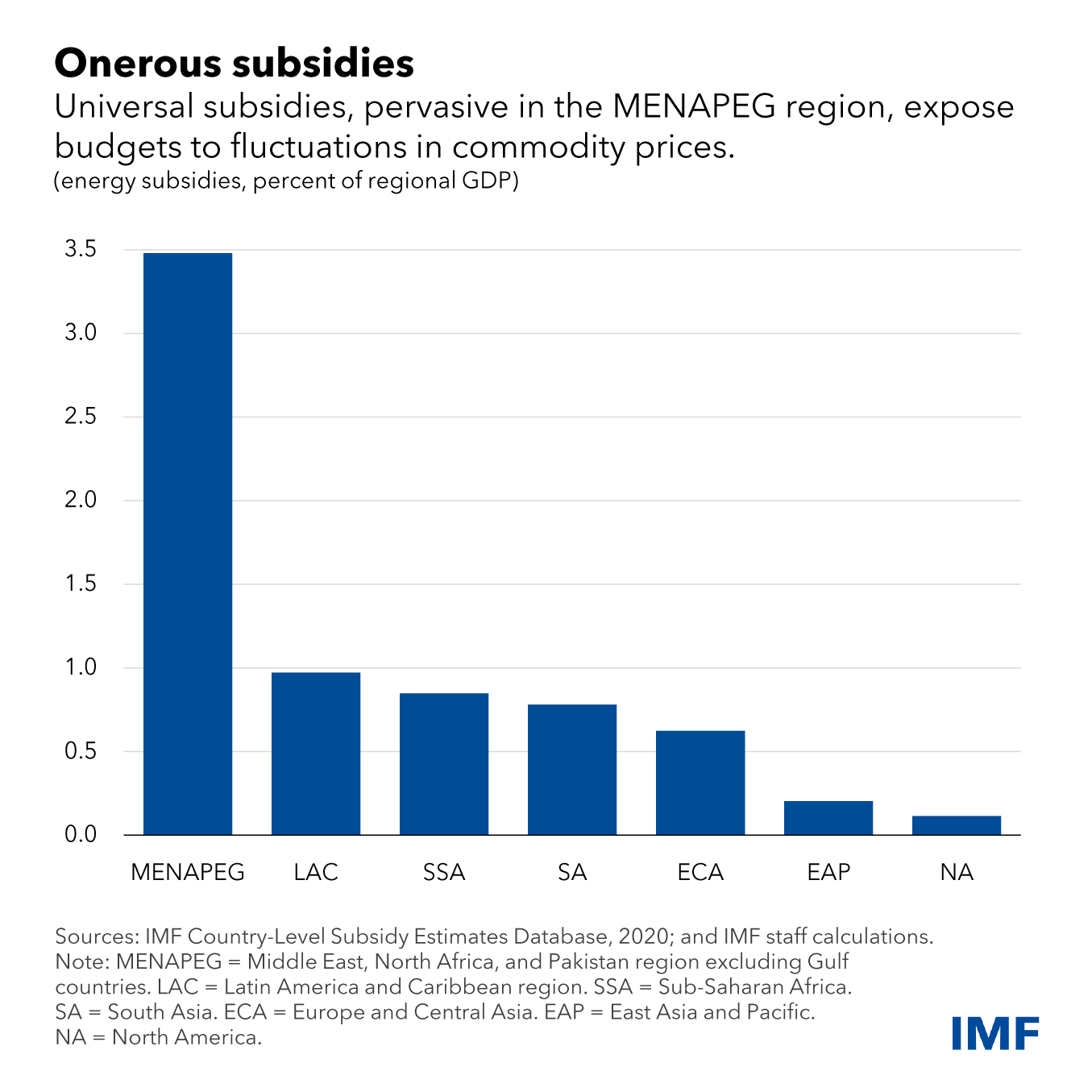

There are multiple factors behind the region’s relatively high exposure to fiscal risks. First is that economic growth is more volatile than in other parts of the world. High reliance on resource revenue among hydrocarbon exporters such as Algeria, Iraq, and Libya, and pervasive universal energy and food subsidies across the region have also exposed budgets to fluctuations in commodity prices.

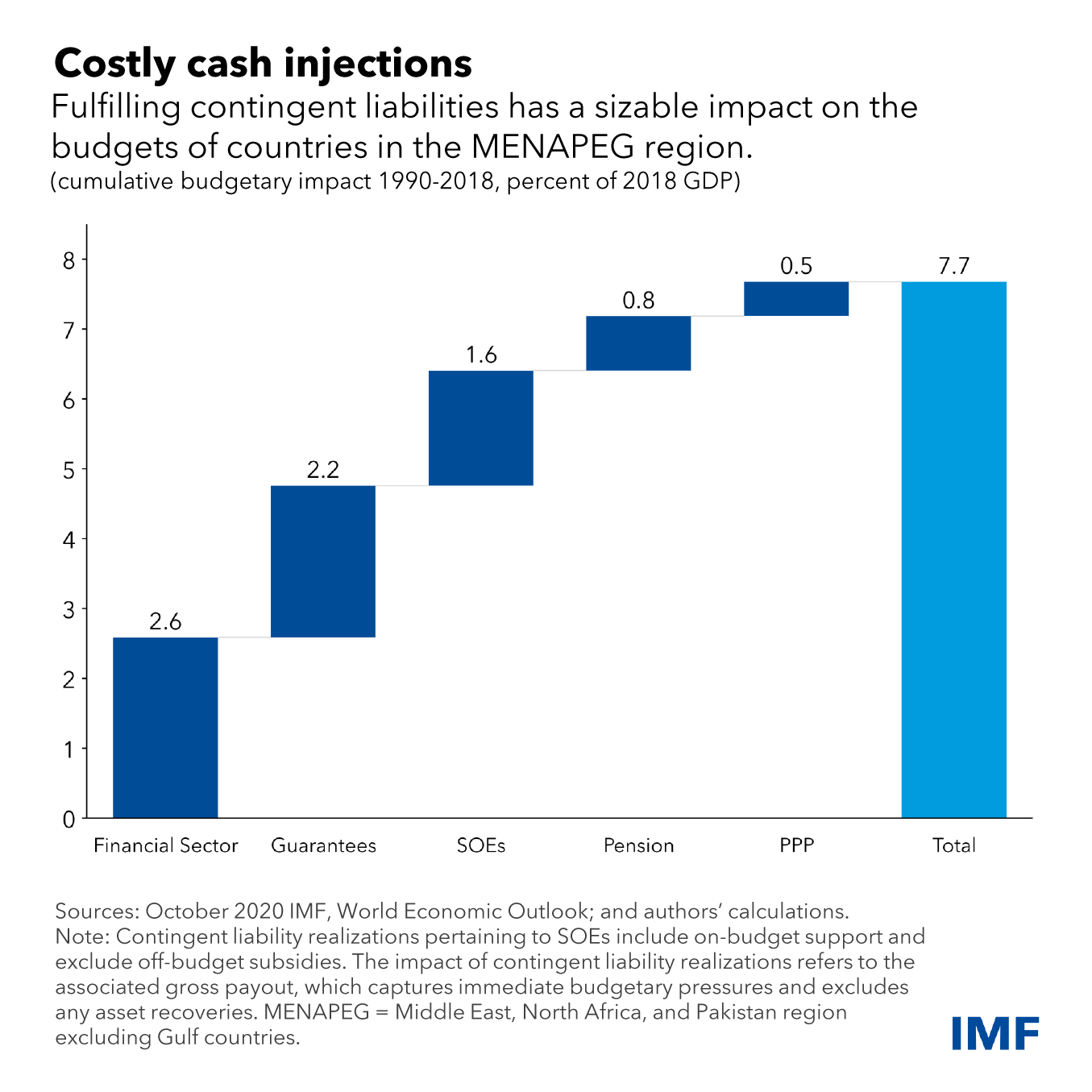

Second, state ownership of non-financial corporations and banks in these countries can generate sizable government obligations that can come due when negative events occur, known as contingent liabilities. For example, a public electric or water utility company that faces large operational losses might require government financial assistance to continue providing services.

Many state-owned enterprises (SOE) in the region are financially weak and require regular government cash injections. This often reflects their role in fulfilling quasi-fiscal activities such as selling goods and services at below market rates or creating jobs, rather than being run on a commercially sound basis. Contingent liabilities may also be arise from public-private partnerships (PPPs). For example, certain PPP contracts might require government to compensate a private partner if collections, as in toll road projects, fall short of projections.

Third, the region’s public finances are exposed to rare extreme events that can have large fiscal consequences. For instance, natural and climate disasters such as the catastrophic floods in Pakistan in 2022, extreme droughts in North Africa or social conflict and instability can disrupt economic activities, destroy infrastructure, create additional spending needs, weaken institutional capacity, and displace populations. Damage from natural disasters alone is around $2 billion annually.

Policies

Against this background, governments across the region are strengthening their capacity to analyze and manage fiscal risks. For example, some governments have set up dedicated macro-financial units and developed fiscal risk statements (Egypt) or achieved progress on mapping fiscal risks (Jordan), monitoring SOEs (Tunisia) and implementing risk mitigating measures (Iraq).

However, governments still need to take steps to enhance fiscal risk data collection, identification, analysis, and management capacity.

First, it is particularly urgent to address data gaps through systematic collection of financial information on SOEs, guarantees, PPPs and other sources of contingent liabilities to inform a transparent assessment of fiscal risks. Once sufficient data has been gathered, modeling techniques such as fiscal stress tests can be deployed to deepen understanding of fiscal risks, the probability of their materialization and their potential impact.

Second, governments should consider mitigation measures. These involve a combination of direct controls, for example, well-calibrated ceilings on the issuance of government guarantees, and indirect measures to discourage risky activities, such as charging fees to beneficiaries of guarantees.

Third, Governments can further enhance resilience to shocks by building buffers for unexpected expenditures and medium-term fiscal frameworks using well-defined debt and deficit anchors. The IMF offers a range of tools and capacity development projects to support national authorities to strengthen their ability to analyze and manage fiscal risks.

Economic reforms can help address fiscal risks at the source. For instance, stronger macroeconomic frameworks can lessen growth volatility. Governance reforms and asset divestment can moderate contingent liabilities or lower the odds of their materialization. And improved budget processes reduce the likelihood of surprises.

Given various uncertainties, fiscal risks in the Middle Eastern and North African countries cannot be fully avoided. However, better risk awareness and stronger fiscal risk management will reduce budgetary surprises and provide firm ground for long-term development policies.